Impostor Syndrome

Karina Evans, Advanced Healthcare Scientist, Queen Alexandra Hospital Portsmouth

Despite degrees, promotions, or praise, many professionals still find themselves haunted by the quiet fear of not being good enough; a phenomenon known as impostor syndrome, where self-doubt overshadows even the strongest evidence of success.

Impostor syndrome is often described as persistent feelings of inadequacy, the fear of being discovered as a fraud, and the tendency to attribute achievements to luck rather than skill. In these moments, external evidence of competence (good performance reviews, strong exam results, successful projects) fails to match the internal narrative.

Who can be affected by Impostor Syndrome?

The short answer is anyone. However, some people are more vulnerable than others. Research suggests that personality, upbringing, and social context can all increase susceptibility. These influences do not directly cause impostor feelings, but they create conditions where self-doubt is more likely to thrive.

Personality traits – Perfectionism and a heightened tendency towards anxiety increase vulnerability, as individuals focus on flaws and downplay achievements (Todd, 2025).

Family background – Inconsistent praise or high parental expectations can make it harder to internalise success (Chua, 2025).

Minority and first-generation status – Systemic barriers, lack of role models, and reduced belonging heighten impostor feelings (LaPalme et al., 2022; Salari et al., 2025).

Academic and professional environments – High-pressure settings, constant comparison, and hidden struggles reinforce self-doubt, particularly among women and later-year students (Shinawatra, 2023).

A survey by the Executive Development Network (2023) found that up to 78% of healthcare professionals had experienced impostor syndrome. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 30 studies involving over 11,000 participants reported an overall prevalence of 62% among health service providers, with higher rates in more recent studies (Salari et al., 2025). Similar patterns have been observed in medical and postgraduate students, suggesting that academic and clinical environments may intensify impostor feelings (Bravata et al., 2020; Shinawatra, 2023).

What can trigger impostor syndrome?

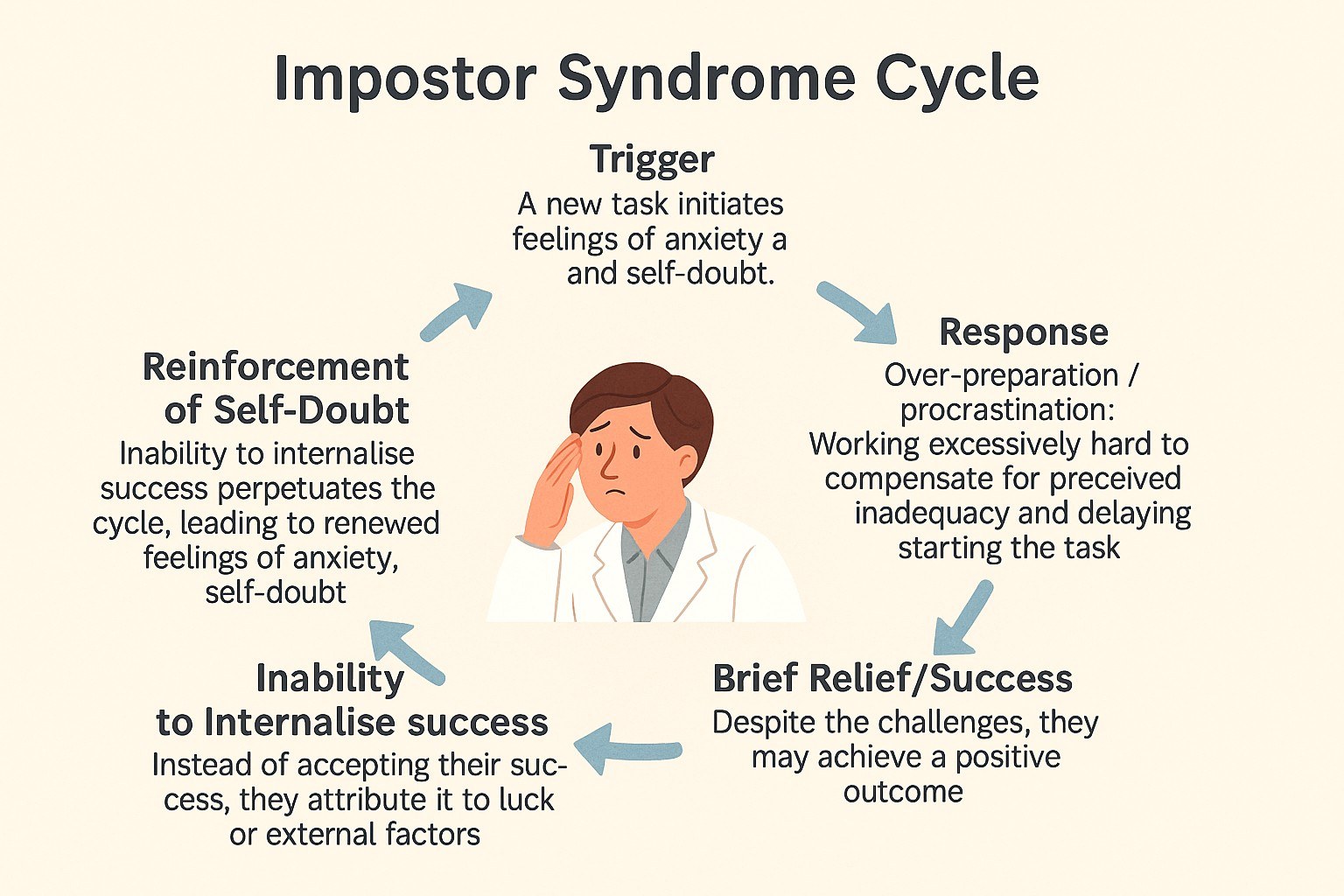

For many, impostor feelings emerge in response to specific situations. These moments act as catalysts, heightening insecurity and pushing individuals to question whether they truly deserve their success. Common triggers include:

Transitions and new challenges – New roles or responsibilities often heighten self-doubt (Royal College of Nursing, 2025; The BMJ, 2021).

Perfectionism – Unrealistic standards lead to dismissing success and magnifying mistakes (Clance, 1985; Female Factor, 2023).

Comparisons – Measuring against peers can make struggles feel isolating (Social Connectedness, 2022; University of Strathclyde, 2023).

Fear of failure – Anxiety about mistakes drives overwork and self-doubt (STP Perspectives, 2020; Institute of Biomedical Science, 2025).

Hidden struggles – Success is visible, but difficulties are often concealed, reinforcing impostor beliefs (Johns Hopkins University, 2022; Vigneshwaran et al., 2020).

What does impostor syndrome look like?

Impostor feelings often reveal themselves through patterns of thought and behaviour. While these vary between individuals, research highlights several common themes:

Over-preparing, working excessively or procrastinating – Spending excessive time on tasks, or delaying them, due to fear the outcome will not be good enough (Clance and Imes, 1978; Bravata et al., 2020; Huecker et al., 2023).

Avoiding help-seeking – Hesitating to ask for support in case it exposes gaps in knowledge or ability (Chen and Son, 2024).

Discounting success – Attributing achievements to luck, timing, or external factors rather than ability (Brauer and Proyer, 2022).

Avoiding opportunities – Turning down promotions or new projects for fear of failure or not belonging (Ménard and Chittle, 2023).

Managing Impostor Syndrome

Although it can feel overwhelming, a range of strategies can help reduce the impact of impostor syndrome. These do not eliminate the feelings entirely but can build resilience, improve confidence, and create healthier ways of working:

Recognising and reframing thoughts – Naming impostor feelings and challenging unhelpful self-talk helps break the cycle of self-doubt (Clance and Imes, 1978; Bravata et al., 2020).

Normalising the experience – Discussing impostor syndrome with peers or mentors reduces isolation and highlights its prevalence (Cokley et al., 2018; Chen and Son, 2024).

Setting realistic standards – Shifting from perfectionism towards achievable goals prevents overwork and burnout (Bravata et al., 2020; Taşkıran et al., 2025).

Practising self-compassion – Replacing self-criticism with self-kindness supports healthier self-worth (Neff, 2011; Hutchins and Rainbolt, 2017).

Mentoring and support networks – Structured mentoring and peer support groups improve confidence and reduce impostor feelings, particularly in healthcare and academic environments (LaPalme et al., 2022; Villwock et al., 2016).

Impostor syndrome is complex and deeply personal, yet research makes clear that it is both common and manageable. By recognising what makes us vulnerable, identifying the situations that can trigger these feelings, and adopting practical strategies to respond, we can begin to loosen its hold. For many, the simple act of realising that others share these doubts is often the most powerful step.

My Experience with Impostor Syndrome

Looking back, I can see that impostor syndrome has been a persistent presence throughout much of my personal and professional journey. It was never one single moment, but a series of experiences, comments, and environments that planted and reinforced the belief that I was somehow not quite good enough, no matter what I achieved.

Early experiences

From a young age, I was often praised for being “naturally bright.” I was invited to the gifted and talented programmes at school and told to choose subjects I enjoyed, because if I enjoyed them, I would succeed. The message I absorbed was that ability was innate, not something that could be cultivated through hard work. When I interviewed for Head Girl, I was unsuccessful; although being named Head Prefect was a huge achievement among more than 200 students, I saw it as a consolation prize rather than recognition.

I excelled at GCSEs, but after only six weeks of sixth form college, I dropped out due to anxiety. Instead, I enrolled in a BTEC in Sport Science. Sport was something I was good at, which felt safer than risking failure. I graduated with distinction, but when faced with the choice of pursuing a university education or seeking employment, I opted for a job. Despite wanting to study forensic anthropology since I was 13, I convinced myself I wouldn’t succeed at university. By chance, that job was as a Cytoscreener, the first step into what would become my healthcare career.

Career

On my very first day in cytology, a senior biomedical scientist told me I would struggle with the training because I “only had a BTEC” and not A-levels. They even said they would “put money on me dropping out.” That comment stayed with me for years.

When I was later offered a funded Biomedical Science degree, I turned it down, fearing I wouldn’t manage both the in-house cytology training and academic study. Only after passing my diploma in cervical cytology did I accept the offer. Yet throughout my degree, I felt inadequate, constantly aware of the knowledge gap between me and my peers who had completed A-levels. Even as I achieved first-class honours, I dismissed the determination it took to get there and focused instead on what I lacked.

This pattern followed me. I had the opportunity to present my dissertation as a poster at the 40th European Congress of Cytology (ECC), hosted by the BAC in Liverpool in 2016. My dissertation topic was “Interpretation Bias on Microscopic Evaluation of Cervical Liquid-Based Cytology Samples with Known Positive High-Risk Human Papillomavirus Status”, which in 2016 was an incredibly hot topic in cytology. I withdrew my poster from the ECC because I was terrified it would be torn apart, and that people would discover I wasn’t good enough. Many years later, when I was encouraged to apply for the Scientist Training Programme in Andrology, I spent an entire week doubting myself before submitting my application. I was chosen, but because I was the only applicant, I assumed the team had “settled” for me, rather than my potential and my hard work being nurtured by an incredibly supportive lab manager.

When I began the STP, I felt even more like an impostor. Most of my peers had master’s degrees, many had spent years applying, and I felt I had cheated my way in. The workload was intense: full-time employment, a master’s degree, and a three-year portfolio. But something important shifted during the last three years. As a cohort, we were open about our struggles. We often spoke about impostor syndrome, challenged each other’s self-doubt, and supported one another through the intensity. The shared experience normalised those feelings and helped me set more realistic standards, moving away from perfectionism.

Being successful in securing the band 7 scientist role and becoming lead scientist for both cytology and andrology, while still in the midst of my STP training, felt like madness at times. Still, it also demonstrated just how much I was capable of. I drew heavily on the resilience and self-awareness I had developed through the STP, using those experiences to ensure that I communicated openly with my team about how I was feeling. I was honest in acknowledging that there were moments when I could not give 100% because of my varied commitments, but I balanced this by consistently praising their ability to keep the laboratory and outpatient clinic running smoothly. Their professionalism and reliability gave me the confidence to juggle both roles, while also teaching me the value of transparent communication and collective achievement.

As my training is almost at an end, I have found that managing impostor syndrome makes it much easier to recognise my achievements and accept that the STP has been incredibly hard. For the first time, I can look back and acknowledge that I have genuinely had to work my backside off to achieve what I have. This is something I was unable to do after finishing my BSc, when self-doubt overshadowed the level of dedication and perseverance it took to succeed.

Joining the BAC Executive

Even as I gained more experience, impostor thoughts persisted. When I first considered applying to the BAC Executive, I saw myself as “too little” in cytology – at the time, I was a band 6 with much still to learn. My first attempt was unsuccessful, and I was secretly relieved. When I applied again in 2023, a consultant even told me they would be surprised if I were successful; this only reinforced my doubts. Yet I was successful, and since joining, I have launched the BAC LinkedIn page, helped shape the membership survey, and managed social media for events. Though I am the most junior member, I have learned to recognise that my contributions still add value.

Reflection

Writing this blog has been both difficult and enlightening. Revisiting these moments reminded me of how much impostor syndrome has shaped my life, but also how far I have come. I laughed at myself for missing deadlines to draft this piece (procrastination at its finest) and for over-preparing / excessively working by going way over the top with references and almost doubling the intended word count. Those very habits are hallmarks of impostor syndrome, and catching myself in the act made me smile.

Perhaps the most positive outcome is how it has shaped my leadership style. I recognise impostor feelings in my colleagues and actively work to challenge them. We celebrate achievements, highlight effort, and acknowledge that struggles are normal. In doing so, I hope to create a team culture where people feel valued rather than doubtful.

Impostor syndrome has been both a burden and a teacher. It has made me reflective, empathetic, and determined to acknowledge not just the achievements, but the hard work that lies behind them. Slowly, I am learning to accept praise, to recognise that success is rarely accidental, and to remind myself, as I encourage others, to look back at just how far we’ve come.

References

Brauer, K. and Proyer, R.T., 2022. The impostor phenomenon and causal attributions of positive feedback on intelligence tests. Personality and Individual Differences, 194, 111663. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111663 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Bravata, D.M., Watts, S.A., Keefer, A.L., Madhusudhan, D.K., Taylor, K.T., Clark, D.M., Nelson, R.S., Cokley, K.O. and Hagg, H.K., 2020. Prevalence, predictors, and treatment of impostor syndrome: a systematic review. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(4), pp.1252–1275. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05364-1 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Chen, S. and Son, L.K., 2024. High impostors are more hesitant to ask for help. Behavioral Sciences, 14(9), 810. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14090810 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Chua, S.M., 2025. Impostor syndrome, associated factors and impact on wellbeing. BMJ Open, 15(7), e097858. Available at: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/15/7/e097858 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Clance, P.R., 1985. The impostor phenomenon: overcoming the fear that haunts your success. Atlanta: Peachtree Publishers.

Clance, P.R. and Imes, S.A., 1978. The impostor phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 15(3), pp.241–247. Available at: https://www.paulineroseclance.com/pdf/ip_high_achieving_women.pdf [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Cokley, K., McClain, S., Enciso, A. and Martinez, M., 2013. An examination of the impact of minority status stress and impostor feelings on the mental health of diverse ethnic minority college students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 41(2), pp.82–95. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2161-1912.2013.00029.x [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Executive Development Network, 2023. Survey on impostor syndrome in science, healthcare and pharmaceuticals. Executive Development Network.

Female Factor, 2023. My impostor syndrome story: how to overcome it, build confidence & find success. [online] The Female Factor. Available at: https://www.femalefactor.global/post/my-imposter-syndrome-story-how-to-overcome-it-build-confidence-find-success [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Huecker, M.R., Shreffler, J., McKeny, P.T. and Davis, D., 2023. Impostor phenomenon. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK585058/ [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Hutchins, H.M. and Rainbolt, H., 2017. What triggers imposter phenomenon among academic faculty? A critical incident study exploring antecedents, coping, and development opportunities. Human Resource Development International, 20(3), pp.194–214. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13678868.2016.1248205 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Institute of Biomedical Science (IBMS), 2025. Laboratory leadership essentials: lead with confidence, stay authentic. [online] Available at: https://www.ibms.org/resource-hub/event-calendar/laboratory-leadership-essentials-lead-with-confidence-stay-authentic.html [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Johns Hopkins University, 2022. An honest reflection on my impostor syndrome and self-doubt. [online] Johns Hopkins University Student Wellbeing. Available at: https://wellbeing.jhu.edu/blog/2022/04/06/an-honest-reflection-on-my-imposter-syndrome-and-self-doubt/ [Accessed 15 August 2025].

LaPalme, M.L., Radke, H.R.M. and Crisp, R.J., 2022. Beyond performance: Understanding impostor phenomenon in pre-service educators. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 838575. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.838575 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Ménard, A.D. and Chittle, L., 2023. The impostor phenomenon in post-secondary students: a review of the literature. Review of Education, 11(2), e3399. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3399 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Neff, K.D., 2011. Self‐compassion, self‐esteem, and well‐being. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(1), pp.1–12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00330.x [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Royal College of Nursing (RCN), 2025. Seven steps to overcome impostor syndrome. RCN Wellbeing Magazine. [online] Available at: https://www.rcn.org.uk/magazines/Wellbeing/2025/Apr/Seven-steps-to-overcome-imposter-syndrome [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Salari, N., Khaledi-Paveh, B., Rajabi, A., Bazrafshan, M., Kazeminia, M., Mohammadi, M., Shohaimi, S. and Vaisi-Raygani, A., 2025. The global prevalence of impostor phenomenon among health service providers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Medical Education, 25(1), p.260. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-06700-9 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Shinawatra, P., 2023. Exploring factors affecting impostor syndrome among medical clinical students. Behavioral Sciences, 13(12), p.976. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/bs13120976 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Social Connectedness, 2022. Unmasking impostor syndrome: a journey to self-belief. [online] Social Connectedness. Available at: https://www.socialconnectedness.org/unmasking-imposter-syndrome-a-journey-to-self-belief/ [Accessed 15 August 2025].

STP Perspectives, 2020. Impostor syndrome – what is it? [online] STP Perspectives. Available at: https://stpperspectives.wordpress.com/2020/07/28/impostor-syndrome-what-is-it/ [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Taşkıran, E., Gündüz, B. and Bulgan, G., 2025. Self-esteem, impostor phenomenon, proactive personality and psychological capital among university students. BMC Psychology, 13, 210. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-025-02898-4 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

The BMJ, 2021. Impostor syndrome. BMJ, 375, n3048. Available at: https://www.bmj.com/content/375/bmj.n3048 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

University of Strathclyde, 2023. Feeling like an impostor is not a syndrome. [online] University of Strathclyde Inspire Blog. Available at: https://www.strath.ac.uk/workwithus/strathclydeinspire/blogs/feelinglikeanimposterisnotasyndrome/ [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Villwock, J.A., Sobin, L.B., Koester, L.A. and Harris, T.M., 2016. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. International Journal of Medical Education, 7, pp.364–369. Available at: https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5801.eac4 [Accessed 15 August 2025].

Vigneshwaran, K., Rekha, R., Sivapalan, A., Fong, Y. and Kadirvel, S., 2020. Prevalence of impostor phenomenon and its association with anxiety and depression among medical students. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 9, p.211. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32080403/ [Accessed 15 August 2025].