Black Lives Matter - a little-known heroine

Article from BAC Executive member Mrs Sue Mehew

Question: do you know who this is?

Answer - This is one of very few pictures of Henrietta Lacks (born 1st Aug 1920 – died 4th Oct 1951.)

Background:

Whilst I knew of the HeLa cell line, I did not know anything about Henrietta Lacks until 2014 when I started researching adenocarcinoma of the cervix to put together a workshop and lecture on Glandular Abnormalities to run at our Update Courses and discovered a sobering history. Allow me to expand a little...

Henrietta Lacks was an African-American woman whose cervical cancer cells were taken from her body without her knowledge and are the source of the widely used HeLa tissue cell line.

Photo from the Museum of the Moving Image website

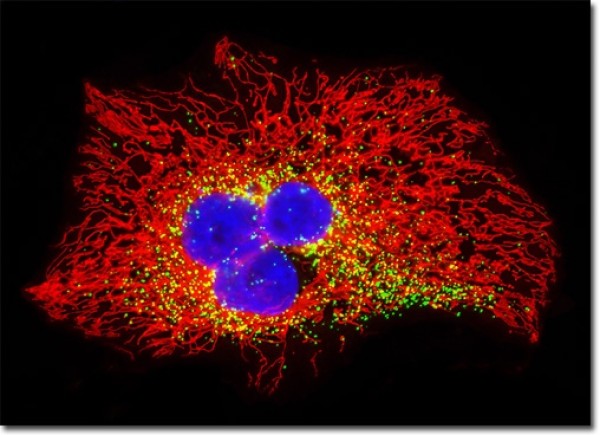

Fluorescence Digital Image Human Cervical Adenocarcinoma Cells (HeLa Line)

Henrietta was born Loretta Pleasant in Roanoke, Virginia, USA on 1st Aug 1920.

She worked on a tobacco farm from an early age. She married her cousin David Lacks and they later moved to Maryland as a family so that David could work at Bethlehem Steel, a factory that provided work for African American men during WWII. Sadly, she died of cervical adenocarcinoma at the young age of 31. (1)

Clinical History:

- She presented with a “knot” feeling just before and during her pregnancy with her 5th child (born September 15 1950)

- A few months after delivery she started bleeding abnormally

- At her GP she tested negative for Syphilis

- Referred to the Gynaecology department John Hopkins Hospital - the only hospital in the area that treated black patients

- February 1951 - A biopsy of the mass on Lacks' cervix (undetected during pregnancy and previous examinations) was taken for histological assessment. Lacks was told that she had a malignant epidermoid carcinoma of the cervix, but later told she had been misdiagnosed and actually had an adenocarcinoma.

- Treated with radium tube inserts - small glass tubes of the radioactive metal secured in fabric pouches—called Brack plaques—which were sewn into place to the cervix.

- After several days, the tubes were removed and she was discharged from John Hopkins with instructions to return for X-ray treatments as a follow-up.

- During radiation treatments two samples of Henrietta's cervix were removed—a healthy part and a cancerous part—without her permission or knowledge.

- The cells from her cervix were given to Dr. George Otto Gey - Head of tissue culture research at John Hopkin’s who was searching for an immortal cell line. Henrietta’s cancerous cells not only survived but multiplied at an extraordinary rate and became “HeLa”, from Henrietta Lacks- the first immortalised tissue cell line (2).

- After Lacks' death, Gey asked Mary Kubicek, his laboratory assistant, to take further HeLa samples while Henrietta's body was at Johns Hopkins' mortuary.(3)

The Lacks family only learned about the HeLa cells in 1973, when a scientist contacted family members, hoping to learn about the family's genetics in order to differentiate between HeLa cells and other cell lines because a large portion of other cell cultures had become contaminated by HeLa cells(4,5).

In the 1980s, the Lacks family medical records were published without family consent and in a similar case the California Supreme Court upheld the right to commercialize discarded tissue in the 1990 case Moore v. Regents of the University of California.

In 1996, Morehouse School of Medicine held its first annual HeLa Women's Health Conference to give recognition to Henrietta Lacks, her cell line, and "the valuable contribution made by African Americans to medical research and clinical practice"(6). The mayor of Atlanta declared the date of the first conference, October 11, 1996, "Henrietta Lacks Day".(1)

In 1998, the BBC screened an award-winning documentary on Lacks and the HeLa; Rebecca Skloot wrote a book in 2010 on the subject, called The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks(1) , then in 2017, a biopic based on the book was aired on HBO after consulting with Lacks’ sons - David Lacks, Jr. and Zakariyya Rahman, and her granddaughter Jeri Lacks(7). These publications each contributed to raising awareness of Henrietta Lacks’ unwitting but enormous contribution to medical science.

Some organizations that have profited from HeLa have since publicly recognized Henrietta Lacks’ contributions to research. The Lacks family has been honored at the Smithsonian Institution and the National Foundation for Cancer Research.

In February 2010, Johns Hopkins released the following statement concerning the cervical samples that were taken from Lacks without her consent:

"Johns Hopkins Medicine sincerely acknowledges the contribution to advances in biomedical research made possible by Henrietta Lacks and HeLa cells.

It’s important to note that at the time the cells were taken from Mrs. Lacks’ tissue, the practice of obtaining informed consent from cell or tissue donors was essentially unknown among academic medical centers.

Sixty years ago, there was no established practice of seeking permission to take tissue for scientific research purposes. The laboratory that received Mrs. Lackss’ cells had arranged many years earlier to obtain such cells from any patient diagnosed with cervical cancer as a way to learn more about a serious disease that took the lives of so many.

Johns Hopkins never patented HeLa cells, nor did it sell them commercially or benefit in a direct financial way. Today, Johns Hopkins and other research-based medical centers consistently obtain consent from those asked to donate tissue or cells for scientific research."

Morgan State University granted Lacks a posthumous honorary degree and in 2010, Dr. Roland Pattillo a faculty member of Morehouse School of Medicine who had worked with George Gey donated a headstone for Lacks’ unmarked grave.

The HeLa case raised questions about the legality of using genetic materials without permission. Neither Lacks nor her family granted permission to harvest her cells, which were then cloned and sold.

In 2013, German researchers published the genome of a strain of HeLa cells without permission from the Lacks family. Then later that year the National Institutes of Health (NIH) granted the Lacks family control over how data on the HeLa cell genome would be used. Two members of the Lacks family formed part of the NIH’s HeLa Genome Data Access working group, which reviewed researchers’ applications for access to the HeLa sequence information.

HeLa cells continue to make an invaluable contribution to molecular science today - used for cloning; to develop various drugs including those used to treat cancer; Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Herpes Simplex virus (HSV); Parkinson’s disease and hundreds of other diseases as well as producing Polio and HPV vaccines. In total they are involved in more than 11,000 patents!

References:

1. Skloot, Rebecca (2010), The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, New York City: Random House, p. 17, ISBN 978-1-4000-5217-2CS1

2. Hayflick, Leonard (March 4, 2010). "Myth-busting about first mass-produced human cell line". Nature. 464 (7285): 30

3. Gold, Michael (1986). A Conspiracy of Cells: One Woman's Immortal Legacy-And the Medical Scandal It Caused. SUNY Press. p. 20

4. Ritter, Malcolm (August 7, 2013). "Feds, family reach deal on use of DNA information". Seattle Times. Retrieved 2016-12-31.

5. Schwab, Abraham P.; Baily, Mary Ann; Hirschhorn, Kurt; Rhodes, Rosamond; Trusko, Brett (2013-08-15). Rhodes, Rosamond; Gligorov, Nada; Schwab, Abraham Paul (eds.). The Human Microbiome: Ethical, Legal and Social Concerns. Oxford University Press. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9780199829422

6. 2011 First Year Book Program - The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks University of Maryland. Retrieved 2016-09-26

7. Stanhope, Kate (2016-05-02). "Oprah Winfrey to Star in HBO Films' 'The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks’".

Sue Mehew, Consultant Healthcare Scientist in Cytology and Scottish Cytology Training School Director, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh.

Photo from the Molecular Expressions™ website